A two-year-old girl passed away at Hadassah-University Medical Center, Ein Kerem, 10 days after she was hospitalized in serious condition due to complications from measles. She had been connected to ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation). Her death marks the eighth in the current outbreak, all of whom were unvaccinated children under the age of two and a half.

The outbreak, which began in April, was initially reported in Jerusalem, Beit Shemesh, and Bnei Brak, and has since spread to additional cities, including Nof Hagalil, Harish, Modi’in Illit, Kiryat Gat, Ashdod, and Safed. The Health Ministry has now designated nine cities as active outbreak zones.

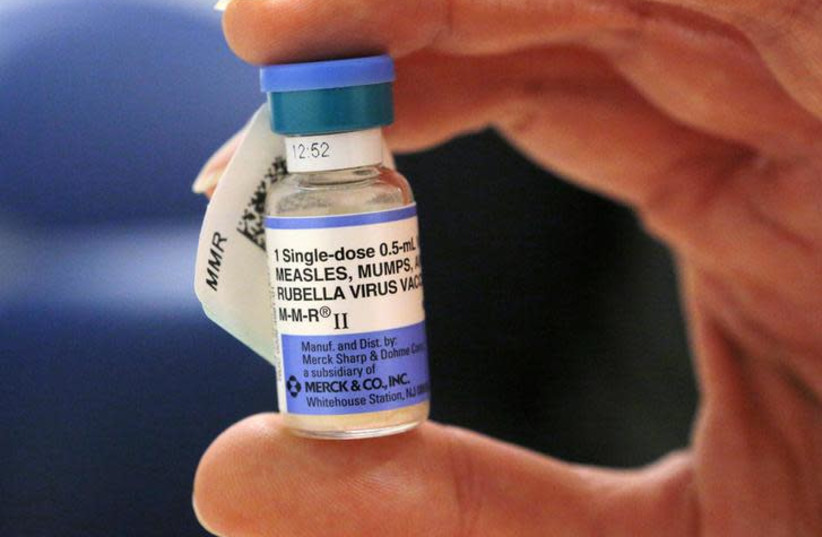

The ministry said that most of the infected had not received the measles vaccine and stressed that all of the severe cases and fatalities could have been prevented through vaccination.

Vaccination campaign intensified

In response to the rising numbers, the Health Ministry has launched a nationwide campaign aiming to reach 95% vaccination coverage among children aged one to six. A national vaccination command center, known as Mashlat, was set up to coordinate the effort in collaboration with the health funds, family health centers (Tipat Halav), and local municipalities.

To support the effort, more than 200 nurse shifts have been added in the past three months, with 50 additional nurses expected to be recruited. Eleven dedicated vaccination centers have been opened, and a mobile vaccination unit now operates daily in cities with particularly low coverage.

Eighty-four primary clinics across the country now offer measles vaccines to the general public, including to non-registered patients, with extended evening hours.

Since the launch of the renewed campaign, 216,000 vaccine doses have been administered, 111,000 of them in outbreak areas. The national vaccination rate for the first dose has increased to 89%, up from 83% at the start of the year.

Sharp increases in Jerusalem, Beit Shemesh

Vaccination rates have risen significantly in the cities first affected. According to the ministry, Jerusalem has seen a 500% rise in vaccinations compared to the same period last year, while Beit Shemesh recorded a 630% increase.

In Jerusalem, first-dose coverage has grown from 77% to 83%, and in Beit Shemesh from 72% to 82%. The ministry’s mobile vaccination unit, which operates five days a week, has so far conducted 32 field days, primarily in Beit Shemesh and other neighborhoods with low vaccination rates.

Tackling vaccine misinformation

In parallel with the vaccination drive, the Health Ministry has taken action to counter false and misleading information about the measles vaccine. In recent months, leaflets, voice messages, and social media posts have circulated, urging parents, especially in insular communities, not to vaccinate their children.

The ministry has asked the Israel Police and heads of health institutions to take enforcement action against those distributing the misinformation. “This is a serious phenomenon that requires a determined response, as the spread of misleading information can prevent people from receiving life-saving treatment,” the ministry said in a letter to enforcement agencies.

Religious leadership joins effort

To support the campaign, the ministry has secured endorsements from senior ultra-Orthodox rabbis and community leaders. Letters encouraging vaccination were distributed by the chief rabbis, the Badatz Eda Haredit, and Rabbis Zilberstein, Hirsch, and Lando, as well as medical advisers Rabbi Firer and Rabbi Cholak.

The dangers of measles

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease with one of the highest transmission rates globally, with more than 90% of unvaccinated individuals exposed to an infected person contracting the virus. It spreads through airborne droplets expelled when an infected person coughs or sneezes, which makes it particularly dangerous in crowded or unvaccinated communities.

Symptoms typically appear one to two weeks after exposure and include high fever, dry cough, runny nose, conjunctivitis, and a distinctive rash that begins on the face and spreads across the body. While many recover within days, infants, pregnant women, and immunocompromised individuals are at greater risk of severe complications, including pneumonia, encephalitis, and even death.

A rare but fatal complication, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), may develop years after an individual has recovered from measles.

Guidelines for vaccination and exposure

According to the national immunization program, individuals born in 1978 or later should have received two doses of the measles vaccine, the first at 12 months and the second in first grade. Children under one are not routinely vaccinated, but in cases of exposure or international travel, they may be given an early dose between six and 11 months. This dose must be repeated later as part of the standard schedule.

Children up to age six are vaccinated at Tipat Halav clinics, while older children and adults receive vaccines through their health funds. Those who have not received both doses, and whose most recent dose was more than four weeks ago, are advised to complete the vaccination.

Adults born before 1957 are considered immune, as they are presumed to have been exposed to measles in childhood.

Post-exposure measures

Following exposure to measles, the ministry's recommendations vary by age, vaccination status, pregnancy, and immune condition. Individuals over six months old who are not immunocompromised should receive an active MMR vaccine within 72 hours.

Infants under five months, pregnant women who are not vaccinated, and severely immunocompromised individuals should be given immune globulin, known as passive immunization, either intramuscularly or intravenously within six days of exposure. Infants aged six to 11 months who missed timely vaccination are also eligible for passive immunization.

Those who receive passive immunization must wait at least six months before receiving an active vaccine. Anyone exposed to the virus who has not been vaccinated or who received the vaccine too late must isolate at home during the incubation period, which lasts two to three weeks, or up to 28 days for those treated passively.