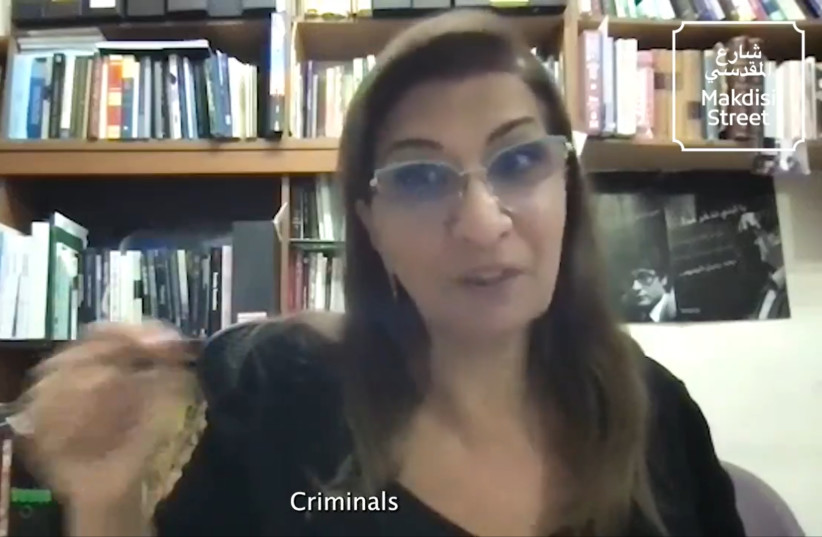

If you thought that Prof. Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian would be left without a job after the inflammatory, antisemitic remarks that led to her suspension from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU), think again.

In recent weeks, it has been loudly reported that Prof. Shalhoub-Kevorkian has now returned to lecturing, this time at Princeton University as a visiting scholar, and is teaching a course titled “Gender, Reproduction and Genocide.” According to descriptions of the course, it will address what is called “the biological and social capacity of Palestinians to exist,” through a comparative lens between Gaza and the Holocaust.

Because this subject has passed quietly under the media’s radar, it is time to put it before the public in Israel and abroad.

We are talking about a lecturer who was suspended in Israel for statements regarded as anti-Zionist and antisemitic, and who was even questioned in a criminal investigation on suspicion of incitement – and she secures a position at one of the world’s most prestigious academic institutions, which declares its commitment to academic freedom and freedom of expression.

Princeton University owes answers

The answer Princeton University owes its student body – and us – is this: What is this professor’s right to present a course built on a false, extreme and antisemitic viewpoint? And what is the academic institution’s responsibility toward the society in which it operates?

Shalhoub-Kevorkian presents herself as an academic with research experience, mainly in criminology, society, and violence in the Israeli-Palestinian context.

In 2024, she was detained on suspicion of incitement after signing a petition calling to “abolish Zionism” and claiming that Israel was carrying out “genocide in Gaza.”

HU suspended her following these statements and noted that this was a “dangerous precedent” for academic freedom in Israel.

Now, she works at Princeton in the center for academic and interdisciplinary freedom. The course she is expected to teach is reported to deal, according with comparisons between Gaza and genocide, claims of an Israeli “reproductive assault” on Palestinians, and gender, family and reproduction as arenas of struggle.

The course will discuss key issues, such as academic freedom vs institutional responsibility. A lecturer’s right to express a critical – even controversial – position is essential to academic freedom. Universities are places where narratives that challenge the consensus can and should be heard, and that is a good thing.

However, when a public position is considered extreme, identified with a call to overthrow a political framework (such as Zionism), and accuses Israel of genocide against a minority, questions arise:

Is this still critical scholarship, or is it political mobilization and is the institution obligated to apply limits and safeguards so that it does not become a platform for incitement and one-sided discourse?

In recent years, criticism has been leveled at Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s research, and journalists have raised questions about research oversight bodies.

Investigative reporter Omri Maniv argued that her work relies mainly on interviews with Palestinian children, rests on sweeping assumptions, and that some of its conclusions are “baseless.”

When such weighty comparisons are made – like those between Gaza and the Holocaust or the Armenian genocide – rigorous research, sourced facts, and transparent methodology become acute. A course that rests on such claims must be very clear about its methodology and the distinction between the lecturer’s political stance and factual analysis.

The fact that a lecturer who was suspended in Israel for false antisemitic statements against the state finds employment at a leading US academic institution is a sign that academic freedom and the freedom to work in academia are not always aligned with basic human fairness.

It also signals an effort to cultivate hostile, illogical, and false ideas – the very ideas for which she was suspended from HU. I have already written about how Shalhoub-Kevorkian’s campaign of slander and delegitimization against Israel is nothing short of a scandal, and that she should have been prosecuted for incitement.

Her new platform at Princeton gives her an even broader stage from which to spread her false, poisonous views. For the Israeli public, Holocaust memory is sacred. A lecturer who demeans Israel and claims that “genocide is being carried out in Gaza” uses language that sows division and discord. This is a declaration that “the Palestinian body lives under attack not only militarily but socially, gender-wise and biologically.” That is plain antisemitism.

Academia must preserve a balance between freedom of expression and responsibility in teaching. When a course deals with such sensitive, inflammatory subjects – and with hatred – the use of terms such as “genocide” require detailed explanation and a clear boundary between academic research and personal agendas.

The course Prof. Shalhoub-Kevorkian is to teach at Princeton is nothing less than an attempt at thought engineering. For the wider community, these developments must serve as a warning sign.

When a lecturer in Israel is questioned over her remarks and still manages to continue teaching in the United States, it requires a reexamination of the relationship between academia and lecturers who spread falsehoods under the guise of “academic research.”

This article will be sent to Princeton University with a request for clarification: How can a lecturer such as Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, who was questioned for incitement in Israel, continue to teach at the prestigious Princeton University in the United States?

The writer is CEO of Radios 100FM, an honorary consul and deputy dean of the Consular Diplomatic Corps, president of the Israel Radio Communication Association, and a former IDF Radio monitor and NBC correspondent.