In 1983, a friend told me about an artist who was showing the first few pages of a groundbreaking handwritten and illuminated Haggada on parchment that he was commissioned to create. As David Moss – a Jerusalemite who made aliyah that year – described his deeply researched, inventive and innovative use of Hebrew lettering and imagery, I was struck by his enthusiasm and his creativity. It was a memorable meeting which I’ve carried with me for the many decades that I’ve followed Moss’s development and career. Moss, a fifth-generation Ohio Jew born in Youngstown in 1946, was raised in Dayton in a home overflowing with creativity instilled by his father, Jack Moss, a composer, poet, inventor, writer and musician. He attended a liberal arts school, St. John’s College in Santa Fe, where he devoted himself to the classics of the western world. After college, he wanted to immerse himself in his own Jewish civilization and set off to Israel to prepare for enrollment at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America.It was in Jerusalem that Moss experienced what he calls, “his magical moment.” A local Torah scribe calligraphed the Hebrew alphabet on a scrap of paper and handed it to him. He describes his deep, visceral response to these letters. He began copying them, composing words and inscribing Biblical passages.

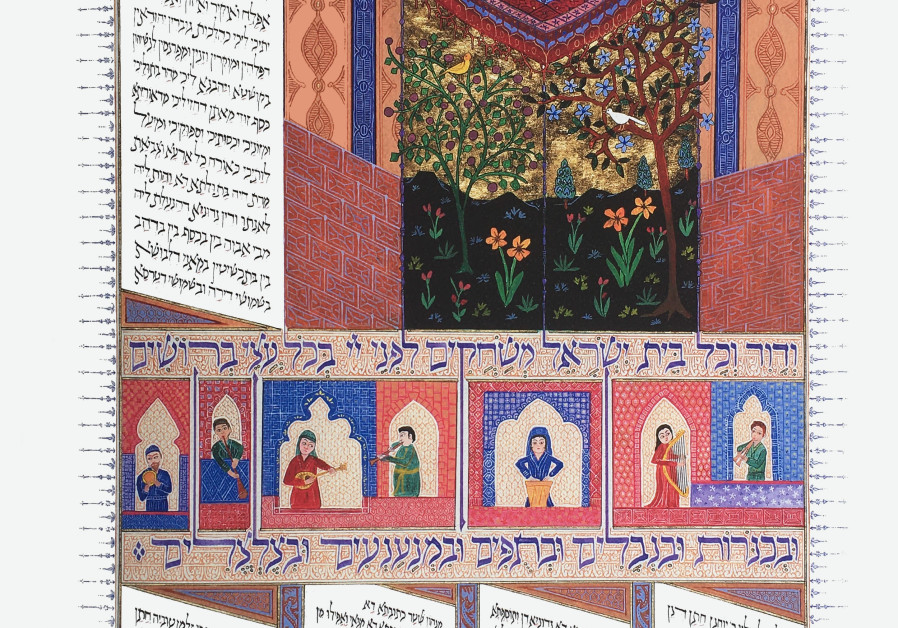

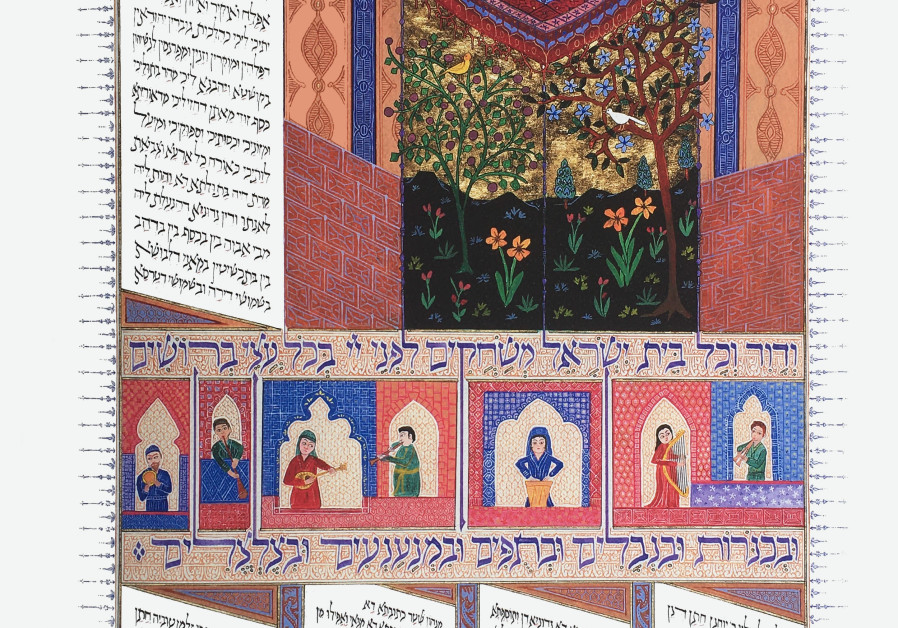

In 1983, a friend told me about an artist who was showing the first few pages of a groundbreaking handwritten and illuminated Haggada on parchment that he was commissioned to create. As David Moss – a Jerusalemite who made aliyah that year – described his deeply researched, inventive and innovative use of Hebrew lettering and imagery, I was struck by his enthusiasm and his creativity. It was a memorable meeting which I’ve carried with me for the many decades that I’ve followed Moss’s development and career. Moss, a fifth-generation Ohio Jew born in Youngstown in 1946, was raised in Dayton in a home overflowing with creativity instilled by his father, Jack Moss, a composer, poet, inventor, writer and musician. He attended a liberal arts school, St. John’s College in Santa Fe, where he devoted himself to the classics of the western world. After college, he wanted to immerse himself in his own Jewish civilization and set off to Israel to prepare for enrollment at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America.It was in Jerusalem that Moss experienced what he calls, “his magical moment.” A local Torah scribe calligraphed the Hebrew alphabet on a scrap of paper and handed it to him. He describes his deep, visceral response to these letters. He began copying them, composing words and inscribing Biblical passages.  Moss attributes his entire, multifaceted artistic career to this moment and to the explosive, creative power he intuitively sensed to be present in these 22 letters. “As I was falling in love with the Hebrew letters, I came to learn about an antiquated Jewish art form – the hand-illuminated marriage contract – the ketubah. I saw examples of the charming, lovingly created folk art ketubot from the Middle East, and the exuberant baroque contracts from Italy,” he says. “I asked about who was creating these today, and was informed that this art form had died out years before and the ketubah had become a drab, printed form filled in by the rabbi and hidden away in a drawer by the couple.”Moss was determined to revive this beautiful Jewish art. He started by making ketubot for young friends getting married. People saw the results and began to commission him. Word began to spread when he wrote the article on ketubah-making in the first Jewish Catalog. The real break came in the early 1970s when the editor of National Jewish Monthly, the B’nai B’rith magazine, became enamored of David’s unique combination of tradition and contemporary expression and ran three cover stories on Moss’s ketubot within a few years. For Moss, the creation of a ketubah is an intimate collaboration between a couple and himself as he interviews them about all aspects of their relationship, their Jewish commitments, their family, and their dreams for their marriage. All this he seeks to synthesize in the final work. The scope of his work in this field is conveyed in a book he produced called Love Letters. The ketubot, reproduced include exquisite, detailed floral patterns, delicate paper-cut borders, hand-gilded lettering, bold modern graphics, intricate micrographic designs incorporating whole biblical books and whimsical fantasies. Nanette Stahl, Judaica Curator of the Yale Library comments: “David’s art is exquisite. He single-handedly reintroduced ketubah illumination into modern Jewish life and has created ketubot of stunning beauty and majesty.”The artistic techniques Moss honed in his ketubot both for newly-wed couples and for anniversaries served him well for the major work for which he is probably best known, The Moss Haggada. The few pages I had seen ended up becoming a 100-page, large format manuscript which took three full years to complete Moss defines his artistic process, as one of head, heart and hand and the Haggada is a prime example of this. “By ‘head’ I mean a deep immersion in the texts and ideas of our literary tradition. To be Jewishly authentic a work must be firmly based in our sources.” He spent nearly the entire first year just studying Jewish sources on the development of the Haggada over the centuries, its traditional and scholarly commentaries and its art history in the medieval illuminated manuscripts in whose shadow he sensed he was working.His second principle is “heart.” He explains: “This represents the creative part of my work. I imbue every work with a fresh, surprising innovation for the viewer. For every section of the Haggada I sought to find an inventive new approach.”For the first page, Moss meditated on the very notion of beginnings. He realized that the Exodus itself was a beginning – the birth of the Jewish people – and that every beginning was essentially about potential. He summarizes: “Every beginning contains the whole.” As the border of page one he wrote out the entire text the Haggada in two intertwining micrographic strands. This also exemplifies his final principle – the hand – ”my obsessive striving for perfect crafting of every work.”To dramatize the verse, “In each and every generation, you must see yourself as if you personally came out of Egypt,” Moss depicted small portraits of Jews from “each and every generation” throughout history – nine men on one page and nine women on the facing page. Between each portrait he affixed an actual Mylar mirror. When the book is closed each Jew sees himself or herself. As we open the page we can actually see them seeing themselves in the facing mirrors, and then when fully open, we see ourselves in the mirrors.In Aumie Shapiro’s review in the London Jewish Chronicle, we read: “When I handled it, I trembled because what I saw was, in my view, the greatest Haggada ever produced.”The manuscript was completed in 1986 and delivered to Richard and Bea Levy, the couple who commissioned it. But in a sense, that was just another beginning with even more potential.When the late Neil and Sharon Norry of Rochester saw photographs of the Haggada, they immediately decided it could not just be hidden away in a collector’s home. They established Bet Alpha Editions to create a perfectly faithful, limited edition facsimile replica in Verona, Italy and subsequently, a trade and deluxe editions were produced making the work widely accessible.

Moss attributes his entire, multifaceted artistic career to this moment and to the explosive, creative power he intuitively sensed to be present in these 22 letters. “As I was falling in love with the Hebrew letters, I came to learn about an antiquated Jewish art form – the hand-illuminated marriage contract – the ketubah. I saw examples of the charming, lovingly created folk art ketubot from the Middle East, and the exuberant baroque contracts from Italy,” he says. “I asked about who was creating these today, and was informed that this art form had died out years before and the ketubah had become a drab, printed form filled in by the rabbi and hidden away in a drawer by the couple.”Moss was determined to revive this beautiful Jewish art. He started by making ketubot for young friends getting married. People saw the results and began to commission him. Word began to spread when he wrote the article on ketubah-making in the first Jewish Catalog. The real break came in the early 1970s when the editor of National Jewish Monthly, the B’nai B’rith magazine, became enamored of David’s unique combination of tradition and contemporary expression and ran three cover stories on Moss’s ketubot within a few years. For Moss, the creation of a ketubah is an intimate collaboration between a couple and himself as he interviews them about all aspects of their relationship, their Jewish commitments, their family, and their dreams for their marriage. All this he seeks to synthesize in the final work. The scope of his work in this field is conveyed in a book he produced called Love Letters. The ketubot, reproduced include exquisite, detailed floral patterns, delicate paper-cut borders, hand-gilded lettering, bold modern graphics, intricate micrographic designs incorporating whole biblical books and whimsical fantasies. Nanette Stahl, Judaica Curator of the Yale Library comments: “David’s art is exquisite. He single-handedly reintroduced ketubah illumination into modern Jewish life and has created ketubot of stunning beauty and majesty.”The artistic techniques Moss honed in his ketubot both for newly-wed couples and for anniversaries served him well for the major work for which he is probably best known, The Moss Haggada. The few pages I had seen ended up becoming a 100-page, large format manuscript which took three full years to complete Moss defines his artistic process, as one of head, heart and hand and the Haggada is a prime example of this. “By ‘head’ I mean a deep immersion in the texts and ideas of our literary tradition. To be Jewishly authentic a work must be firmly based in our sources.” He spent nearly the entire first year just studying Jewish sources on the development of the Haggada over the centuries, its traditional and scholarly commentaries and its art history in the medieval illuminated manuscripts in whose shadow he sensed he was working.His second principle is “heart.” He explains: “This represents the creative part of my work. I imbue every work with a fresh, surprising innovation for the viewer. For every section of the Haggada I sought to find an inventive new approach.”For the first page, Moss meditated on the very notion of beginnings. He realized that the Exodus itself was a beginning – the birth of the Jewish people – and that every beginning was essentially about potential. He summarizes: “Every beginning contains the whole.” As the border of page one he wrote out the entire text the Haggada in two intertwining micrographic strands. This also exemplifies his final principle – the hand – ”my obsessive striving for perfect crafting of every work.”To dramatize the verse, “In each and every generation, you must see yourself as if you personally came out of Egypt,” Moss depicted small portraits of Jews from “each and every generation” throughout history – nine men on one page and nine women on the facing page. Between each portrait he affixed an actual Mylar mirror. When the book is closed each Jew sees himself or herself. As we open the page we can actually see them seeing themselves in the facing mirrors, and then when fully open, we see ourselves in the mirrors.In Aumie Shapiro’s review in the London Jewish Chronicle, we read: “When I handled it, I trembled because what I saw was, in my view, the greatest Haggada ever produced.”The manuscript was completed in 1986 and delivered to Richard and Bea Levy, the couple who commissioned it. But in a sense, that was just another beginning with even more potential.When the late Neil and Sharon Norry of Rochester saw photographs of the Haggada, they immediately decided it could not just be hidden away in a collector’s home. They established Bet Alpha Editions to create a perfectly faithful, limited edition facsimile replica in Verona, Italy and subsequently, a trade and deluxe editions were produced making the work widely accessible. Moss’s Tree of Life Shtender project exemplifies his love of the overlooked and the underappreciated. Shtender is the Yiddish word for a simple, personal wooden lectern/stand. Dozens are found in yeshivot and traditional synagogues. Moss calls them “the overlooked workhorses” of Judaica objects. He was intrigued by the artistic potential of this object and compared the Shtender’s use to his triad of head, heart and hand. The Shtender was indeed the place of both prayer and study spiritually uniting the Jewish heart and head. But he imagined an unprecedented kind of Shtender that would serve as a small treasure chest to house all our hands-on daily, weekly and annual ritual objects. Intimately collaborating with the fine wood artist, Noah Greenberg of Safed, David produced an exquisite Shtender that contains each object carved with realistic plants of the Land of Israel including a siddur, a charity box, a tefillin box, Shabbat candelabrum, challah board, Kiddush set, havdalah set, shofar, lulav, etrog, hanukkiah, Purim Megillah, Seder plate and omer counter. Over 100 examples are in homes, museums and synagogues. From the three-dimensional Shtender, it was a bold but natural step into architecture. David sees parallels with his original work on Ketubot. “The process is surprisingly similar. But instead of interviewing a couple, I’m listening to everyone in an organization to determine exactly what their mission, goals, dreams, vision, challenges are. For me a building should not just house an institution but must play an active role in enhancing and furthering its organizational goals, just like their board, staff and programming do.”David has been on the architectural design team for both remodeling projects such as The UJA Federation of New York and Congregation Beth Shalom, Seattle as well as for new construction like the Fuchs Mizrachi School in Cleveland, the Hillel Foundation, UCLA and the Akibah Yavne Academy, Dallas. His vision ranges from the macro to the micro. For the campus in Dallas he laid out the buildings to reflect their modern orthodox and Zionist ideology. Jaynie Schultz, one of the funders, said: “I cannot adequately express the genius of this man. David took what could have easily turned into a basic school building, and by understanding the character and hearts of the entire school community, has helped us design what will clearly become one of the most beautiful campuses in the southwest.” The school was awarded the architectural prize for best design of all construction projects in Texas for 2006.

Moss’s Tree of Life Shtender project exemplifies his love of the overlooked and the underappreciated. Shtender is the Yiddish word for a simple, personal wooden lectern/stand. Dozens are found in yeshivot and traditional synagogues. Moss calls them “the overlooked workhorses” of Judaica objects. He was intrigued by the artistic potential of this object and compared the Shtender’s use to his triad of head, heart and hand. The Shtender was indeed the place of both prayer and study spiritually uniting the Jewish heart and head. But he imagined an unprecedented kind of Shtender that would serve as a small treasure chest to house all our hands-on daily, weekly and annual ritual objects. Intimately collaborating with the fine wood artist, Noah Greenberg of Safed, David produced an exquisite Shtender that contains each object carved with realistic plants of the Land of Israel including a siddur, a charity box, a tefillin box, Shabbat candelabrum, challah board, Kiddush set, havdalah set, shofar, lulav, etrog, hanukkiah, Purim Megillah, Seder plate and omer counter. Over 100 examples are in homes, museums and synagogues. From the three-dimensional Shtender, it was a bold but natural step into architecture. David sees parallels with his original work on Ketubot. “The process is surprisingly similar. But instead of interviewing a couple, I’m listening to everyone in an organization to determine exactly what their mission, goals, dreams, vision, challenges are. For me a building should not just house an institution but must play an active role in enhancing and furthering its organizational goals, just like their board, staff and programming do.”David has been on the architectural design team for both remodeling projects such as The UJA Federation of New York and Congregation Beth Shalom, Seattle as well as for new construction like the Fuchs Mizrachi School in Cleveland, the Hillel Foundation, UCLA and the Akibah Yavne Academy, Dallas. His vision ranges from the macro to the micro. For the campus in Dallas he laid out the buildings to reflect their modern orthodox and Zionist ideology. Jaynie Schultz, one of the funders, said: “I cannot adequately express the genius of this man. David took what could have easily turned into a basic school building, and by understanding the character and hearts of the entire school community, has helped us design what will clearly become one of the most beautiful campuses in the southwest.” The school was awarded the architectural prize for best design of all construction projects in Texas for 2006.

In 1983, a friend told me about an artist who was showing the first few pages of a groundbreaking handwritten and illuminated Haggada on parchment that he was commissioned to create. As David Moss – a Jerusalemite who made aliyah that year – described his deeply researched, inventive and innovative use of Hebrew lettering and imagery, I was struck by his enthusiasm and his creativity. It was a memorable meeting which I’ve carried with me for the many decades that I’ve followed Moss’s development and career. Moss, a fifth-generation Ohio Jew born in Youngstown in 1946, was raised in Dayton in a home overflowing with creativity instilled by his father, Jack Moss, a composer, poet, inventor, writer and musician. He attended a liberal arts school, St. John’s College in Santa Fe, where he devoted himself to the classics of the western world. After college, he wanted to immerse himself in his own Jewish civilization and set off to Israel to prepare for enrollment at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America.It was in Jerusalem that Moss experienced what he calls, “his magical moment.” A local Torah scribe calligraphed the Hebrew alphabet on a scrap of paper and handed it to him. He describes his deep, visceral response to these letters. He began copying them, composing words and inscribing Biblical passages.