We Israelis love kids. We have lots of them, unlike most other countries. In Israel, there are three million children under the age of 18 – nearly one-third of our population. Experts note that Israel’s high female fertility reflects “the peculiar durability of Israel’s fertility, unique in ethnically diverse societies.”

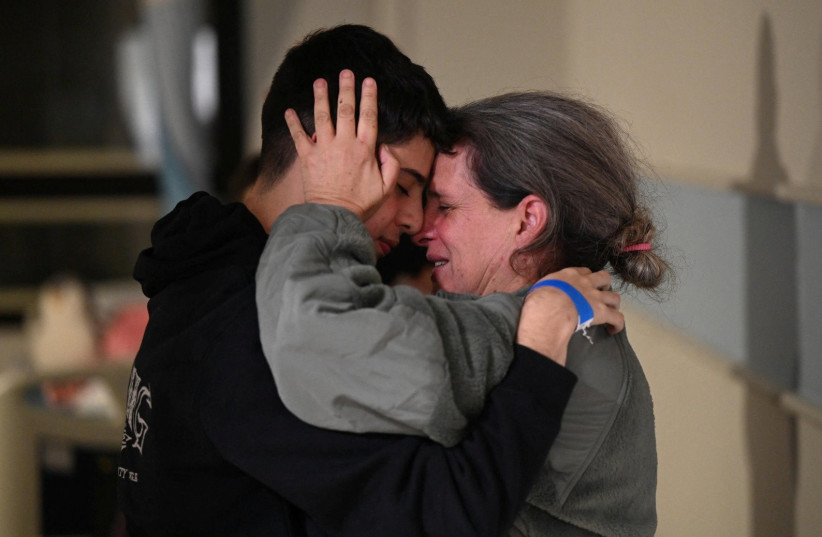

Since October 7, 2023, Israel has been in a bitter multi-front war, under rocket attack. The war continues. Many adults and children have suffered trauma and are dealing with the aftermath.

Parents and grandparents grapple daily with the thorny question of how and how much to speak to their children and grandchildren about the war. Understandably, many of us try hard to shield our children from the horrors of war and to reassure them.

The truth is, our children and grandchildren know a great deal more than we think. Hiding hard truths from them, truths that they already know by talking to other children, may increase their anxiety rather than calm their fears.

I spoke about this with educator and philosopher Prof. Arie Kizel of the University of Haifa’s Faculty of Education. He was recently interviewed by Netanel Gamss in the daily Haaretz.

Gamss wrote: “‘The psychologistic discourse has taken over … Children are scared, of course, just like everybody else, but their fear is intensified by grown-ups,’ declares Prof. Arie Kizel at the start of our meeting, held a few days after the bout with Iran.”

Kizel’s perspective struck a chord. We grownups may be intensifying our children’s fears rather than allaying them. He agreed to an email interview for my column.

The best course I ever took in college was Philosophy 1. It was 65 years ago, yet I still vividly remember the instructor, A.C.R. Duncan, a demanding Scot. I use what I learned from him daily. Logic. Ethics. How to think. How to ask questions. Professor, you are co-founder and president of the Mediterranean Association for Philosophy with Children and have written studies and three books on this subject. Why should we teach philosophy to kids, and how should we do it?

I am against teaching philosophy at a young age. I am in favor of doing philosophy at a young age. Let me clarify the difference. Teaching philosophy is an activity where a teacher instructs students on philosophical material – this is common in Israeli high schools. Doing philosophy, on the other hand, is the practice of engaging in philosophical conversation with young children, using the method we call a ‘philosophical community of inquiry.’ In this approach, nothing is taught, and no philosophers are discussed. Instead, young children are empowered to express their opinions in a structured way.

In one of your articles, you write: ‘Psychologistic discourse attempts to promote calmness: It sees children’s questions about death as representing fear – and thus views it as a problem. Philosophical discourse views the question as a place of wondering and exploration and understands that it stems from intelligent thinking by the child. He won’t express it like the best philosophers, but he does realize, like them, that life is finite.’

Should we parents and grandparents be leveling honestly with kids, telling the truth rather than trying to shield them from it? Because for sure, they know a lot more than we think.

I believe that parents should generally talk less, explain less, and guide less. The notion that we are the knowledgeable ones and thus should guide (on the subject of thinking) is the root of the mistake. Children can think for themselves – at least as well as adults.

If they ask questions, we should direct the question back to them. Then we’ll see that they also know how to practice finding an answer and will usually arrive at the correct and logical one. If not, we can guide them by raising possibilities and asking further questions.

The psychologistic discourse that I’m complaining about views children as helpless, small, incapable, and vulnerable. This perspective demands that we, as adults, intervene in a way that I believe is excessive. I want to distinguish between children who are genuinely harmed due to direct exposure to war or direct trauma – who absolutely require psychological or other professional assistance – and those who have not been directly harmed.

I study and teach creativity. Scientist George Land showed how creativity crashes, from ‘genius’ in five-year-olds, to abysmal in adults. Why? Kids are superb at divergent thinking – ‘there are many solutions.’ We teach convergent thinking in schools: ‘There is only one “right” answer.”

Philosophy is about how to live, how to think, how to act… and how to ask questions. Root cause analysis teaches you to ask seven consecutive questions in an inquiry to get you to truth. Kids do it all the time. In general, kids are resilient – perhaps a lot more than adults. What does this imply for how we deal with the stress of war on kids?

Children think differently than adults. The problem is that adults don’t understand that young children are in crucial stages of their cognitive development, and they interfere with it through excessive and unnecessary guidance. They do this, in my opinion, because they are afraid – what I call a ‘pedagogy of fear.’ They mistakenly believe that children don’t know how to think, aren’t capable, are confused, or are scared. And in doing so, they are profoundly wrong.

Children think correctly, ask good and curious questions, and know how to develop their ways of thinking (even if in a different way from adults). It is fitting that they do this naturally, as they are capable and know how to do it!

Adults should step back slightly during these stages, being less dominant and less controlling. This requires a change in how adults perceive children’s thinking. That is what I have been speaking and writing about for years. It’s very difficult for adults because they have been educated to assist, help, and protect. I understand adults’ concern, but there’s no need to worry when it comes to the thinking processes of children.

Now, regarding wartime or conflict situations. Here, we must differentiate between children and adults who have been directly affected. These individuals require immediate assistance from psychologists and other support professionals. In the first phase, they must be helped urgently and in every possible way.

In the second phase, after several months, philosophical counseling can be introduced to enable them to grapple with life’s questions. This philosophical counseling, which is gaining acceptance in some places, including Israel, differs from psychological counseling; it is less clinical. But I want to emphasize that philosophical counseling should be introduced only after several months for those directly affected by trauma.

However, there are many who have not been directly harmed, and they should be approached differently, removing the ‘psychologistic discourse’ that labels them as victims.

PTSD, asking questions, and children

Clinical psychologist Dr. Debra Kissen has explained: “Studies have shown a correlation with the development of post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD] and avoidance behaviors. In other words, the more one tries not to think about a traumatic event, resists revisiting a traumatic place, and avoids contact with any potential triggers of the traumatic event, the more likely one is to develop PTSD.”

Greek philosopher Socrates taught how to ask questions – moving beyond superficial observations to find underlying causes and principles. Children do this naturally. We adults often lack the patience to answer them.

Arie Kizel has a simple, powerful suggestion. When children ask you a question, ask them one. Explore what they think. Engage them as collaborators in inquiry. They will always surprise you with their insights and creative thinking. Philosophy with children.

In these uncertain times, the attentive presence of loving, reassuring, patient parents and grandparents, engaging openly and honestly about everything, can reduce children’s anxieties and fears.

The second verse of David Da’or’s lovely song “Take Care of the World, Child,” goes: “Take care of the world, child. Don’t think too much because the more you know, child, you’ll only understand less.”

Many parents believe this. I know I did. But it is quite the opposite. The more children know and understand, the more they are reassured, and the less anxious they become.

Talk openly with your kids. I’m betting that what they know and what they think will surprise you.■

The writer heads the Zvi Griliches Research Data Center at S. Neaman Institute, Technion. He blogs at www.timnovate.wordpress.com